Steven Pinker’s The Sense of Style is a great style guide and grammar book for people who are confident with their writing and want to dig deeper

You may have heard of Steven Pinker already if you’re interested in neuroscience, linguistics, and/or watch TED talks. Pinker is a Harvard University professor, linguist, and cognitive psychologist, and he’s proof that even scientists need to write well. His book The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century gives the style guide genre a much-needed update for the new millennium. If you’re looking for a style guide and grammar book that goes beyond the basics, I recommend buying and reading Pinker’s book. In this article, I’ll summarize what Pinker does, as well as provide you with a list of some bad style habits students and professionals might unknowingly be cultivating.

What is Style?

There are many different ways to use words to communicate ideas and emotions to readers. “Style” refers to how you use words. Pinker notes that classic style guides such as The Elements of Style by Strunk and White and Fowler’s A Dictionary of Modern English Usage are now quite old and in their prescriptions for language use largely fail to take into account the fact that language is a tool that changes over time.

Good Writing: Reverse-engineering good prose

One of Pinker’s most useful points should seem like common sense to many people: good writers are, first and foremost, good readers. When they read, however, they’re not merely looking to harvest information. Rather, they’re attuned to how the writer conveys information. They’re attuned, that is, to the writer’s style. Analyzing texts to understand what they’re doing and why they’re effective (or not) at doing it is key to developing your own sense of style and increasing your fluency with the English language. To demonstrate, Pinker presents and analyzes passages from several different writers, offering commentary as to what the writers are doing and what the effects of their choices are. Pinker quotes Oscar Wilde, who says that nothing worth knowing can be taught. Style, Pinker argues, is well worth developing, and although it can’t be taught in the same way a mathematical formula can be taught, it can be cultivated through reading and thinking about not merely what a writer says, but how he or she says it.

A Window onto the World: Classic Style as An Antidote to Stuffy Prose

Pinker writes that “the key to good style, far more than obeying any list of commandments, is to have a clear conception of the make-believe world in which you’re pretending to communicate.” How can writers hope to develop and articulate this “clear conception”? Pinker turns to literary scholars Francis-Noël Thomas and Mark Turner, who, in their book Clear and Simple as the Truth, advocate for what they call “classic style.” Classic style, Pinker explains, is structured by the metaphor of “seeing the world.” Writers attempting to employ classic style aim to “align language with the truth.” When writing in classic style, it’s essential that the writer “knows the truth” and endeavors to give the reader “an unobstructed view of it.” Writing in classic style takes for granted the fact that the reader will recognize the truth when he or she sees it.

The two main elements of classic style are 1) “showing the reader something in the world” and 2) “engaging [the reader] in conversation.”

What do these elements imply? First, if the writer is attempting to show the reader something, there must be something to see. This something to see may be either concrete or abstract, but it’s likely a combination of both. Second, the attempt to engage the reader in conversation implies that the reader is an active participant. The writer does not have to “spell everything out” for the reader, but can count on the reader to be engaged and “read between the lines, catch his drift, and connect the dots.”

Pinker helpfully reminds readers what classic style is NOT:

“Classic style is not a contemplative or romantic style, in which a writer tries to share his idiosyncratic, emotional, and mostly ineffable reactions to something. Nor is it a prophetic, oracular, or oratorical style, where the writer has the gift of being able to see things that no one else can.”

Pinker also explains how classic style is different from the practical style favored by Strunk and White:

“In practical style, the writer and reader have defined roles (supervisor and employee, teacher and student, technician and customer), and the writer’s goal is to satisfy the reader’s need. Writing in practical style may conform to a fixed template (a five-paragraph essay, a report in a scientific journal), and it is brief because the reader needs the information in a timely manner. Writing in classic style, in contrast, takes whatever form and whatever length the writer needs to present an interesting truth.”

Lastly, Pinker emphasizes that classic style is not the same as plain style, in which “everything is in full view and the reader needs no help in seeing anything,” He wisely points out that the difference between prose styles is hardly black and white, and that many (or most) writers blend their styles and tailor their style to their purpose for writing and intended audience.

Importantly, Pinker takes issue with writing advice that exhorts readers to avoid abstraction. The capacity for abstract thought is important part of what makes us human. When writing about abstract concepts in classic style, however, the writer’s goal should be to make those abstract concepts intelligible “as if they were objects and forces that would be recognizable to anyone standing in a position to see them.” To illustrate his point, Pinker quotes excerpts from theoretical physicist Brian Greene’s work to explain the very abstract concept of the multiverse theory to a general audience. Though Greene is a respected scientist, he is also a skilled writer, and it’s likely that his skill as a writer is a critically important reason his work is known to many outside his chosen field.

Pinker enumerates habits that are at odds with classic style, namely “metadiscourse, signposting, hedging, apologizing, professional narcissism, clichés, mixed metaphors, metaconcepts, zombie nouns, and unnecessary passives.”

What are these habits to avoid?

Metadiscourse is “verbiage about verbiage, such as subsection, review, and discussion.” Pinker wisely notes that “Inexperienced writers often think they’re doing the reader a favor by guiding her through the rest of the text with a detailed preview,” when in reality, the opposite is true. One of the reasons that much academic work is impenetrable to the point of seeming ridiculous to a general audience is that its often laden with metadiscourse.

Signposting is a particular form of metadiscourse in which writers “say what you’re going to say, say it, and then say what you’ve said.” Pinker advises writers in the classic style to keep signposting to a minimum. The concept of signposting has its origins in classical rhetoric, and when speaking to an audience, it can often be helpful, as speech vanishes into thin air as it’s spoken. If the listener misses something, it may be gone forever. By signposting, orators can help ensure the listener will hear what they’re trying to say and retain the information they hear. When writing, though, it’s not as necessary, as the reader can simply reread.

Hedging refers to instances of writers who “cushion their prose with wads of fluff that imply that they are not willing to stand behind what they are saying, including almost, apparently, comparatively, fairly, in part, nearly, partially, predominantly, presumably, rather, relatively, seemingly, so to speak, somewhat, sort of, to a certain degree, to some extent, and the ubiquitous I would argue.”

Apologizing refers to self-conscious writers’ habit of complaning about how difficult, complicated, or controversial what they’re doing is.

Professional narcissism involves members of a profession, such as professors or researchers, who in their writing “lose sight of whom they are writing for, and narcissistically describe the obsessions of their guild rather than what the audience really wants to know.”

Clichés are stock phrases laden with images that have gone style. Mixing metaphors refers to the piling on of different clichés. Some examples of clichés and mixed metaphors that Pinker presents are: ““The price of chicken wings, the company’s bread and butter, had risen. Leica had been coasting on its laurels. Microsoft began a low-octane swan song. Jeff is a renaissance man, drilling down to the core issues and pushing the envelope. ” Awful!

Metaconcepts are concepts about concepts, marked by language like “approach, an assumption, a concept, a condition, a context, a framework, an issue, a model, a process, a range, a role, a strategy, a tendency, or a variable.” There is often a way to write without resorting to metaconcepts.

Zombie nouns are words that have undergone nominalization–they’ve been turned into nouns. Pinker gives examples of verbs turning into lifeless nouns: “Instead of affirming an idea, you effect its affirmation; rather than postponing something, you implement a postponement. ” Zombie nouns strip all agency away from verbs, which makes for stuffy prose. When possible, use verbs for actions instead of zombie nouns.

Unnecessary passives involve using the passive voice when not absolutely necessary. An example of active voice: The dog ate the treat. An example of passive voice: The treat was eaten by the dog. Many style guides (and English teachers) caution writers to avoid the passive voice. There are, however, important instances in which you want to use the passive voice. These are instances in which the agent of the action is NOT of primary importance. Here’s a length but useful paragraph by Pinker on the subject:

Often a writer needs to steer the reader’s attention away from the agent of an action. The passive allows him to do so because the agent can be left unmentioned, which is impossible in the active voice. You can say Pooh ate the honey (active voice, actor mentioned), The honey was eaten by Pooh (passive voice, actor mentioned), or The honey was eaten (passive voice, actor unmentioned)—but not Ate the honey (active voice, actor unmentioned). Sometimes the omission is ethically questionable, as when the sidestepping politician admits only that “mistakes were made,” omitting the phrase with by that would identify who made those mistakes. But sometimes the ability to omit an agent comes in handy because the minor characters in the story are a distraction. As the linguist Geoffrey Pullum has noted, there is nothing wrong with a news report that uses the passive voice to say, “Helicopters were flown in to put out the fires.”24 The reader does not need to be informed that a guy named Bob was flying one of the helicopters.”

The Curse of Knowledge

After discussing classic style and outlining some habits to avoid, Pinker writes at length about what he calls “the curse of knowledge,” (i.e. knowing so much about a topic that when you write about it your writing is so laden with jargon and difficult to follow that no general reader has a hope of doing so). Pinker advises you to get people who are NOT experts in your field to read your word and tell you whether or not it’s accessible and clear. Specialized language and jargon should always be explained when writing for a general audience.

The Web, the Tree, and the String

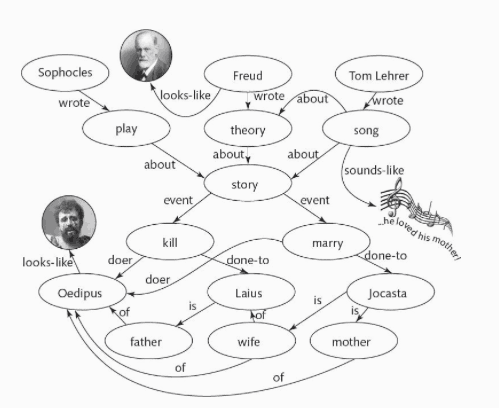

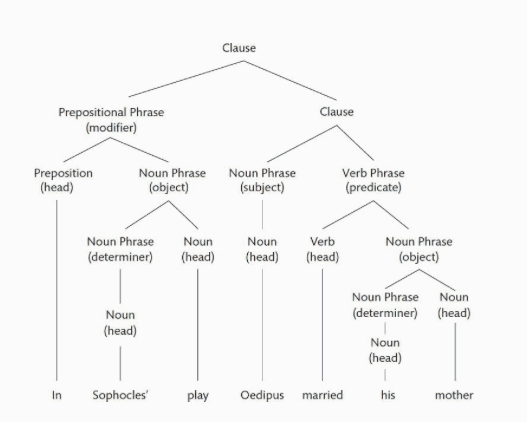

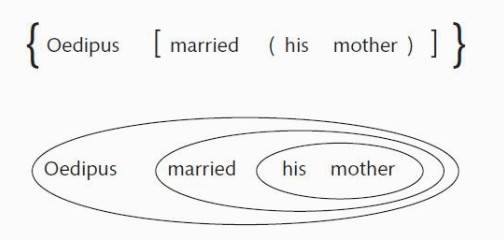

In a discussion on syntax and grammar, Pinker uses the metaphors of the web, the tree, and the string to explain how grammar and syntax work to convey ideas. There exist a web of associations in the writer’s mind, which the writer turns into a string of thoughts by means of a tree of phrases. Here are visual diagrams that will help you understand these metaphors.

The Web

The Tree

The String

Syntax, then, makes order out of chaos. It takes associations and links between words, images, and ideas, and uses a tree of phrases and clauses to produce a string of text aimed at communicating meaning.

Arcs of Coherence

Although individual sentences may be well crafted, a succession of well crafted sentences does not necessarily equate to a coherent or well-crafted paragraph or text. Pinker explains how to ensure sentences form a complete whole by organizing your thoughts before writing. A larger concept can be broken down into smaller concepts, which are broken down into smaller concepts, and so on. Everything must be connected, and the connections must be easy to follow.

Telling Right from Wrong

In the final chapter, Pinker presents the reader with one hundred common grammar and usage mistakes and educates them on how to avoid those mistakes and write properly. This section of the book is the most practical section, and I highly recommend buying The Sense of Style to take advantage of the wealth of information it offers.

* * *

That’s it! If you want to take your writing to the next level, I highly recommend Steven Pinker’s The Sense of Style. If you want more English advice, as well as a plethora of articles on SAT prep, ACT prep, and the college and university application process, check out the rest of our blog. Looking for 1-on-1 ACT or SAT prep tutoring? Want to join an SAT or ACT group class? Contact us today!