Get higher SAT & ACT Writing scores fast with exclusive courses from a perfect-scoring veteran tutor.

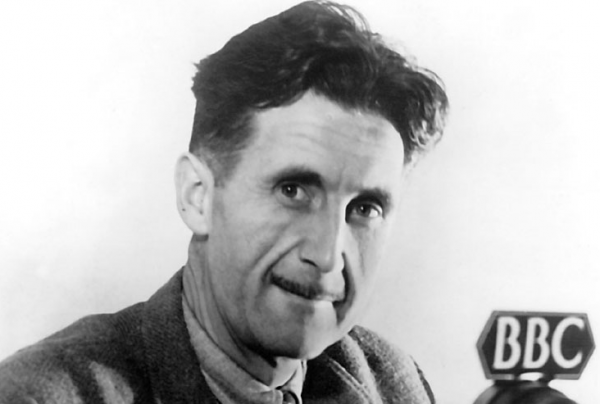

6 Rules for Writers from George Orwell

Writing is a difficult discipline, especially for those just starting out. High school students often struggle to formulate clear, concise, intelligent sentences, and when they’re faced with the task of writing an essay–whether in class or for an exam such as the ACT and SAT essay, or an AP test–they tend to express themselves in a fashion that could use some improvements in clarity and style. If you’re looking for some great writing tips, these 6 rules for writers from George Orwell (of 1984 and Animal Farm fame) will surely prove enlightening and practical. Although Orwell is primarily known for his fiction, his writing rules offer valuable insight and information to writers of all stripes, whether they’re students preparing for the SAT and ACT or fiction writers slogging through the first draft of a manuscript. These 6 writing rules come from Orwell’s brilliant essay “Politics and the English Language,” a blistering critique of vague and rhetorically empty political language, which Orwell views as intentionally circuitous and obfuscating. The essay is a great read, and its criticisms of bloated language ring true in an age in which style has come to trump substance. Let’s take a tour through some of the main points of “Politics and the English Language” and end with Orwell’s list of 6 rules for writers!

The Problem with Writing, in Orwell’s View

At the outset of his essay, Orwell diagnoses the problem with English language writing. Though political rhetoric was at the forefront of his mind when he wrote the essay, Orwell’s critiques apply to all writing. His central claim is that “Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble.” Soon, Orwell will go on to explain the “bad habits” that he mentions, illustrating his points with examples of clunky writing. Though the problem is dire in Orwell’s mind, he is optimistic that language can be fixed, noting that “If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration.” Two of Orwell’s chief complaints are against what he sees as “staleness of imagery” and “lack of precision.” He quotes five examples of turgid prose, and then goes on to discuss four common problems of modern prose.

Four Problems with Modern Prose

In addition to the staleness of imagery and lack of precision of which Orwell complains, there are, in his view, four problems that plague modern prose. They are: 1) dying metaphors, 2) operators or verbal false limbs, 3) pretentious diction, and 4) meaningless words. Let’s take a look at each of the four problems and consider some examples of them.

DYING METAPHORS

Orwell embraces the metaphor as a device that has the potential to enliven prose and explain and evoke concepts and feelings in a fresh, vivid way. But he worries that many metaphors have died and are still in use because writers lazily reach for them so often. Orwell writes:

a huge dump of worn-out metaphors which have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves. Examples are: Ring the changes on, take up the cudgel for, toe the line, ride roughshod over, stand shoulder to shoulder with, play into the hands of, no axe to grind, grist to the mill, fishing in troubled waters, on the order of the day, Achilles’ heel, swan song, hotbed. Many of these are used without knowledge of their meaning (what is a ‘rift’, for instance?), and incompatible metaphors are frequently mixed, a sure sign that the writer is not interested in what he is saying.

How many times have you heard worn-out metaphors such as these? If you find yourself reaching for them, try to invent a fresh image rather than a stale one. Doing so will go a long way toward igniting a reader’s imagination. A writer who is able to engage a reader’s imagination has a better chance of conveying his or her message in a memorable way.

OPERATORS OR VERBAL FALSE LIMBS

It’s critical as a writer to not just choose any word, but rather to choose the right word, every time. Not just any noun: the most specific and precise noun. Not just any verb: the most specific and precise verb. In complaining against what he calls “operators or verbal false limbs,” Orwell makes apparent just how often writers fall back on stock and clichéd language to convey concepts and actions. Orwell writes that operators or verbal false limbs

save the trouble of picking out appropriate verbs and nouns, and at the same time pad each sentence with extra syllables which give it an appearance of symmetry. Characteristic phrases are render inoperative, militate against, make contact with, be subjected to, give rise to, give grounds for, have the effect of, play a leading part (role) in, make itself felt, take effect, exhibit a tendency to, serve the purpose of, etc., etc. The keynote is the elimination of simple verbs. Instead of being a single word, such as break, stop, spoil, mend, kill, a verb becomes a phrase, made up of a noun or adjective tacked on to some general-purpose verb such as prove, serve, form, play, render. In addition, the passive voice is wherever possible used in preference to the active, and noun constructions are used instead of gerunds (by examination of instead of by examining). The range of verbs is further cut down by means of the -ize and de- formations, and the banal statements are given an appearance of profundity by means of the not un- formation. Simple conjunctions and prepositions are replaced by such phrases as with respect to, having regard to, the fact that, by dint of, in view of, in the interests of, on the hypothesis that; and the ends of sentences are saved by anticlimax by such resounding commonplaces as greatly to be desired, cannot be left out of account, a development to be expected in the near future, deserving of serious consideration, brought to a satisfactory conclusion, and so on and so forth.

Do you recognize many of these expressions or the tendency toward them in the speech and prose of today? I bet you do! When reaching for a word, stock phrases like these are easily grasped, and so writers and speakers latch onto them in the interest of continuing to write or speak. To pause, reflect, and choose deliberate language is too difficult and too time-consuming for them. As a result, the reader and the listener both suffer.

PRETENTIOUS DICTION

Another issue Orwell raises with modern prose and political speech is what he sees as an epidemic of pretentious diction. Diction, of course, is word choice, and Orwell singles out the authors and speakers of today for their heavy recourse to fancy words–perhaps to cloud meaning or to achieve an impression of intelligence–over simpler, clearer alternatives. Orwell writes of the problem of pretentious diction:

Words like phenomenon, element, individual (as noun), objective, categorical, effective, virtual, basic, primary, promote, constitute, exhibit, exploit, utilize, eliminate, liquidate, are used to dress up a simple statement and give an air of scientific impartiality to biased judgements. Adjectives like epoch-making, epic, historic, unforgettable, triumphant, age-old, inevitable, inexorable, veritable, are used to dignify the sordid process of international politics, while writing that aims at glorifying war usually takes on an archaic colour, its characteristic words being: realm, throne, chariot, mailed fist, trident, sword, shield, buckler, banner, jackboot, clarion. Foreign words and expressions such as cul de sac, ancien regime, deus ex machina, mutatis mutandis, status quo, gleichschaltung, weltanschauung, are used to give an air of culture and elegance

Piling on pretentious words in one’s writing or speech may delude poor readers and thinkers into believing a writer has something substantial and resonant to say, but it won’t fool most educated readers and thinkers! It’s wise to avoid inflating your writing and thoughts with language like Orwell describes.

MEANINGLESS WORDS

Orwell’s last point of contention against modern prose is what he sees as the proliferation of so-called meaningless words in our discourse. He gives us some examples and explains his point thus:

it is normal to come across long passages which are almost completely lacking in meaning. Words like romantic, plastic, values, human, dead, sentimental, natural, vitality, as used in art criticism, are strictly meaningless, in the sense that they not only do not point to any discoverable object, but are hardly ever expected to do so by the reader. When one critic writes, ‘The outstanding feature of Mr. X’s work is its living quality’, while another writes, ‘The immediately striking thing about Mr. X’s work is its peculiar deadness’, the reader accepts this as a simple difference opinion. If words like black and white were involved, instead of the jargon words dead and living, he would see at once that language was being used in an improper way. Many political words are similarly abused. The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’. The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another.

Much academic writing is padded with meaningless language such as this. Orwell even rewrites a sentence from the Bible in a parodic fashion, mocking the rhetorical tactics and practices of his day. Here is the original version:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

And here is Orwell’s re-imagining of that classic line:

Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

It certainly sounds like a politician wrote it, doesn’t it? Or a stuffy academic writer. Notice how bereft of imagery the second version is. Notice how inflated its words and phrases have become. Orwell has killed what made the original Ecclesiastes line so beautiful, so resonant, so fresh.

Orwell’s 6 Rules for Writers

To remedy the problem of vague, imprecise, and stale language that deadens our prose, and, as a result, kills our capacity to think critically, Orwell has prescribed 6 rules for writers. The best writers, of course, don’t rely entirely on rules. They do, however, study prose and those who make it and come to learn by doing what works and what doesn’t. Here are Orwell’s rules:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

If you take Orwell’s rules into account when composing, your essays, fiction, and speech will be better for doing so. Notice that Orwell freely gives you permission to break his rules. That’s because language is alive. We use it as a tool and as a means of self-expression. Inform your readers; engage them; provoke them; delight them; ask them to think and imagine. Clichés, meaningless jargon, empty phrases, and the like will only blunt your communicative powers. Don’t cloud meaning with nonsense. Rather, strive for precision, clarity, concision, and originality. Heed Orwell’s 6 rules for writers! Before you know it, you’ll be writing incredible prose. Your essays will sparkle. Your stories will sing. Your speech will compel. Good luck, and keep writing.

Read the full text of George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” online for free here.

* * *

For more writing advice, as well as a plethora of SAT and ACT prep tips, check out the rest of our blog. And if you need help on your SAT and ACT Essays, download this course.

Looking for 1-on-1 ACT or SAT prep tutoring to help you with the college application process? Want to join an SAT or ACT group class? Contact us today for a free, personalized consultation.

We’re perfect-scoring tutors with years of experience helping students achieve the SAT and ACT scores they need to make their college dreams a reality!